“When you arrive at your room, you’ll have paper plates, plastic silverware, styrofoam cups, linen, two rolls of toilet paper,” she pauses. “But I’d bring your own toilet paper, they’ll give you the shitty, half–ply stuff.” She finishes, “trashcan and liners, and a cleaning pack to sanitize. Return the key fob in the envelope you receive it in.” I scramble to type down her instructions in my notes app. She rattles off a list of numbers that I can call: Axis Apartments Front Desk, Residential and Hospitality Services, Student Health Services, CAPS, and Penn Police, just in case. Cheerfully: “Call me back at this number if you have any more questions.” The call ends. A few hours later, I lug my suitcase four blocks to Axis Apartments, pausing every few steps to catch my breath. It’s only ten days, but I packed a kettle, collapsible lamp, and comforter, recommendations from former isolators. Arriving at Axis, an Allied Security guard helps me carry my luggage up to the second floor landing—he tells me that COVID–19 patients aren’t allowed to use the elevators, because people actually live on the upper floors. I search for my key among the name–labeled red plastic bags crammed onto a small table on the landing: Sam…Paige…Eleanor…Sienna. Finally, I spot mine, Mira. Now starts ten days in isolation. On Nov. 30, 2021, Penn’s COVID–19 Response Team sent an announcement to the University community about a campus–wide increase in the COVID–19 positivity rate. The following day, the Office of Student Affairs sent a message encouraging student organizations to postpone social events. According to Penn’s Fall 2021 COVID–19 dashboard, between Nov. 28 and Dec. 18, 2021, a total of 431 Penn students tested positive for COVID–19. On Dec. 18, 2021, a total of 414 students were in isolation, with 88% available capacity in Penn’s isolation spaces. But during this time, students recall that Penn’s isolation buildings were exceeding capacity. We reached out to the Campus Health COVID–19 Management Team Lead Christopher Blake Felix DiDonato multiple times, as well as Senior Associate Director of Residential and Hospitality Services Courtney Dombroski, who redirected us to Penn Business Services Director of Communications and External Relations Barbara Lea–Kruger, who introduced us to Penn Wellness’s Mary Kate Coghlan, who was unable to get back to us with a response from Penn Wellness. SHS shared limited information about COVID testing and isolation policies, which was already available through Penn’s COVID FAQs. No one was able to speak with us about reports about the conditions in isolation dorms. Amid the uptick in COVID–19 cases on campus, students isolated in a number of buildings around University City, including dorm buildings, off–campus apartment buildings, and other locations owned by Penn. The experience was an added source of stress amid finals and the end of the fall 2021 semester—for many of these students, once they tested positive, they felt as if they became a second thought to the University.

Paola Camacho (C ’24) sits alone in her isolation room at Axis Apartments, on hold with a representative from Student Health Services. It’s just one of the many confusing phone calls she’s had since testing positive for COVID–19. After performing with her on-campus dance group at Carnegie Hall on Dec. 10, Paola went to get a COVID–19 test the next day, Saturday, Dec. 11. Knowing she had just attended a high–risk event, she also decided to self–quarantine, sleeping separately from her roommate. By Monday, she still hadn’t received the results, so she went to get another test. She received a negative test on Monday afternoon and that evening, saw friends and slept in the same room as her roommate. But the next morning, Tuesday, Dec. 14, Paola woke up to a red pass and a message that she had tested positive for COVID–19. Soon after, she received a call from the University telling her she would need to move to Axis, an isolation dorm. Paola explained to the University representative that she had never gotten her test results from Saturday but had tested negative the day before. Paola was told that it was likely that her test from Monday was a false negative, that her positive test from Saturday was unlikely to be an error, and that she would be isolated. They explained that the probability of a false negative with Penn’s saliva–based PCR tests was much more likely than the probability of getting a false positive. She felt nothing but confusion and anxiety for all the people she had exposed in the past day. “All I could think was ‘Why am I being told I’m positive four days after I got tested?’” says Paola. “It shocks me that the testing system at this school can mess up so badly.” Paola suspects that the delay in receiving her Saturday results was likely the result of timing—Penn’s COVID–19 testing labs are closed on Sundays. “It made me really angry that I could have gotten so many people sick.” Luckily, to her knowledge, no one she saw on Monday tested positive after seeing her. She was also the only person in her dance troupe that tested positive. But the confusing communication from Penn only continued through Paola’s period in isolation. Any time she had a question and she called the phone number given to her upon moving to Axis, she would be transferred multiple times—it seemed that she could never find someone who could answer her questions, and different people would share conflicting information. “They kept asking me, ‘Who was it that you talked with?’ I thought they had a good record of things, but it seemed like it was always on me to refer them to the person who had previously told me certain information,” says Paola. At one point, while on the phone with a representative from SHS, she was informed that the date that she was allowed to leave isolation had changed to Dec. 24—two days later than she had initially been told. Even though she didn’t go into isolation until the 14th, her ten–day isolation period should have begun the day she tested positive. However, when she called to ask whether there was any risk she would be contagious post–isolation, it seemed that the date had been misrecorded—she was now being told she couldn’t leave until Christmas Eve. “For a second, I thought I wouldn’t be allowed to go home. That was my biggest fear—that I would miss Christmas,” says Paola. Eventually, she was able to confirm that she could leave on the 22nd and returned home to her family. Penn’s testing system seems pretty straightforward: Get COVID–19 tests regularly, quarantine if you’ve been exposed to someone who tested positive, if you test positive, get a Red Pass, move into one of Penn’s designated COVID–19 isolation dorms. But Paola’s experience demonstrates that the testing system isn’t as seamless as it’s made out to be.

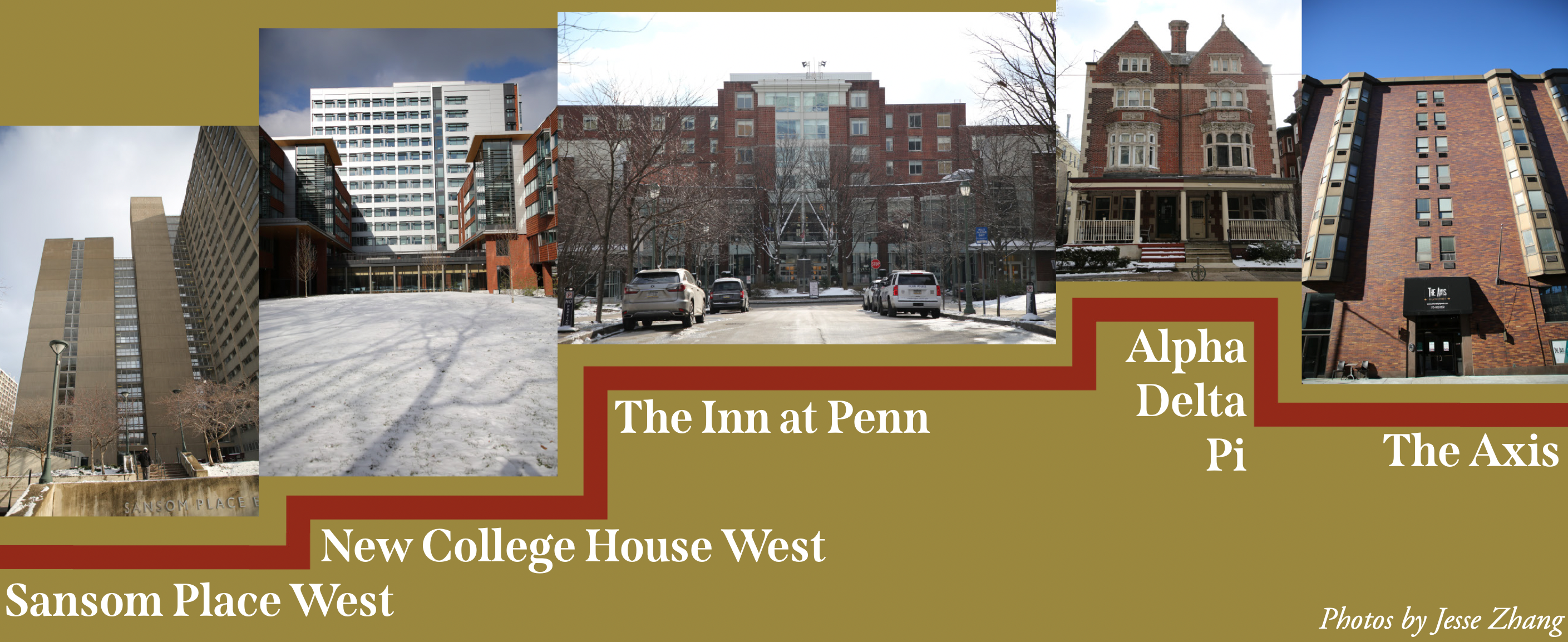

After the first few nights at Axis, I settled into a melancholy routine. Habits that were non–negotiable in my dorm room became optional in isolation. I ate half as many meals as I used to, showered when I was bored (often several times a day), and got dressed if I felt like it. I learned to tiptoe around the stairwell so the security guards wouldn’t hear my pacing and to take walks in the sweet spot of the day so I could catch the sunset over the Schuylkill on my way back. Those walks—usually once per day—saved my body and mind. The first night, a few friends and I reached the southern end of the Schuylkill River Trail, disappointed we couldn't walk farther. We masked up and made it to the art museum at night and the corners of West Philadelphia during the day, musing about the patterns in architecture and drumming up stories about the people we passed on the street. After I graduated from Axis, Paola told me a friend of ours had walked across the entire city, from river to river, just to avoid another hour in isolation. Down the hall from Paola, Maura Pinder (W ’24) counts the hours until Dec. 19, the day her isolation period ends and she can leave her COVID–19 cell. She tested positive on Dec. 9, two days before Paola even got her initial test. But Maura did not arrive at Axis until Dec. 15, the day after Paola. Maura’s isolation was all over the map. The day that Maura tested positive, she received a call from a University representative informing her she would isolate in her room in Harrison College House for the time being—the University didn’t have any isolation spaces available. She self–isolated in her room, putting her roommate, who had received a negative COVID–19 test and with whom Maura shares a bathroom and kitchen, at risk of exposure. On Dec. 10, Maura received a call informing her that she could move to be isolated in the former Alpha Delta Pi house, commonly known as ADPi, which was being used for isolation overflow. But Maura had an online final that day—and ADPi had no WiFi. She remained in Harrison for another night. The next day, Dec. 11, Maura received another call informing her that she had a new option for her isolation location—a room at The Inn at Penn. The next thing she knew, she was lugging her essential belongings down Locust Walk. “No one gave me guidance on what I was supposed to do, what I was allowed to do, what I wasn’t allowed to do. They just gave me my room number and told me to move there,” she says. For the next five days, Maura isolated in her room at The Inn, leaving only to pick up meals left for her in a conference room on her floor. Her main contact was a representative from the University, whom Maura referred to affectionately as her “nurse,” who checked in frequently for the first few days and even gave Maura her personal number should she need anything. But on her fifth day at The Inn, when Maura had three days left in her isolation period, she got a call from an unfamiliar University representative telling her that she needed to move to Axis by the end of the day. Maura explained on the phone this would mean walking through the lobby, potentially exposing guests, and moving all of her belongings on her own in the midst of taking exams and completing final papers. She was still forced to relocate. The notification that she would have to move came completely without warning: No one Maura had spoken to in her past several days in isolation indicated that she might be relocated. Yet again, she was packing up her belongings to inhabit another empty and unfamiliar room. According to the Penn COVID–19 Dashboard, University officials “remain in regular communication” with students who have tested positive and are in isolation. This was not Maura’s experience. Once Maura moved to Axis for her last days of isolation, calls from University representatives seemed to dwindle. “After a while, people just stopped checking in,” she says. “That’s when I started feeling really lonely.” Even though she was only there for three days, Maura’s time at Axis was the hardest. “It did a number on my mental health. It felt never–ending, like I would never get out,” she says. Through isolation, Maura also felt constant concern about exposing other people in the buildings where she was isolating. “I was so worried about giving COVID to security guards when I was at Axis or to people in the lobby when I was at The Inn,” she says. Security guards in Axis were stationed at the staircase on the second floor where Penn students who had tested positive were isolated. Maura says that security guards had minimal PPE, even though they were specifically stationed on floors in Axis where students were sick. Maura spoke with the guards on the isolation floor, who told her that they didn’t receive hazard pay. “It seems really unfair to me that they aren’t offered any additional compensation or resources, and they’re literally amongst kids with COVID–19 for eight hours at a time,” she says. Academic policies for students in isolation were also unclear: One of Maura’s finals was pushed to the spring because it required she take it in person. “There was just no protocol in place for students who had to sit for a proctored final,” says Maura. While the University moved all exams after Dec. 17 online, exams that were scheduled in person on Dec. 17 or before remained—leaving isolated students to take incomplete classes and reschedule in–person exams for the spring if their professors would not accommodate remote exams. Because of this, Maura still has an incomplete in one of her classes from the fall 2021 semester, a lingering source of stress and side effect of being in isolation.

”

I felt paralyzed and cut off from the life I had just a week before. There were often days when I’d go outside [for a walk] and the sky would either be gray or dark—which doesn’t exactly help one feel happy. At the end, you had to return to the Axis. I remember this one walk where I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. I remember being out there feeling like life was meaningless and that the days made no sense and what am I doing? We were about halfway through our quarantine at this point and I felt fine physically, but mentally I was at my worst. And people still ask me, ‘are you all recovered?’ And I am from the disease, but from the mental aspects? Maybe. I really don’t know.

Sam Cheever, C'24

“

When you’re sick you need to take care of yourself, but just given the timing that wasn’t really a possibility. I felt guilty for not being able to study to the best of my abilities, but I also couldn’t force myself to study in the physical and mental state that I was in, so it was just a never–ending cycle of chastising myself and stressing myself out knowing that I wasn’t being productive.

Paige Dendunnen, C'23

“

I was really hoping for emotional or academic support from Penn, but was disappointed. Besides getting an automated message each day asking how I was doing, it didn’t seem like the University cared enough to make sure students such as myself were okay (both mentally and physically). I got pretty sick from COVID, and I’m still not fully recovered. Some of my professors were extremely understanding, but I did struggle to receive any sort of help from one of the departments, which left me feeling overwhelmed and isolated. I already struggle with mental health issues, and it once again felt as though the university did not care.

Eleanor Grauke, C'25

Note: the quotes above have been edited and condensed.

Life in Axis consisted of (1) sleeping, and (2) craving basic necessities. We drank from bathroom sinks and plastic bottles and snacked on Penn–provided treats. Food had to be ordered by midnight the night before we wanted it, so we couldn’t place orders for the first day in isolation. The bag of sustenance we received upon arrival was stocked with some microwaveable oatmeal, chips, a cup of mac n’ cheese, a granola bar, and a mushroom risotto. My boyfriend, a vegan, gave me his risotto and mac n’ cheese. The risottos sat in my fridge until I left Axis. We became used to culinary mishaps. I once ordered a meal with sides and only received the sides. Another time, my grapes were lined with gray fuzz. One day, Paola called me, bursting with frustration and disbelief at the fungus growing in her fruit cup. After that, she didn’t trust the food she was receiving. But ordering outside food was too expensive, so she made do with the food she was given. She lived in fear of another moldy meal. “It’s difficult to be given food from an outside source that you can’t see and trust that it’s sanitary,” Paola says. Maura’s meals were left in a conference room on her floor at The Inn at Penn. One day, the water in the hotel was shut down. “Everyone else in the hotel could leave, but I was stuck there. Fourteen hours without water was rough,” says Maura. Once she made it to Axis, the conditions were even worse, her linens stale from days in isolation and a second move. The thought of a fresh, warm meal felt like a luxury. “I had never been so excited to go to Commons and eat,” says Maura upon her exit from Axis. She returned home to her family shortly after. “When I went home, I was just happy to have clean clothes and clean towels and reliable water,” she says.

Five blocks away from Axis, Heather Bernstein (W ‘24) stares out her window in the old Alpha Delta Pi house, watching dusk envelop West Philadelphia. A few days into isolation after testing positive for COVID–19, her days consist of schoolwork, calling friends, pacing the desolate house and—this. Sitting at her window and watching the world go about its business without a hitch. When Heather contracted COVID–19 in early December 2021, they never imagined that they’d get stuck in an abandoned sorority house, sandwiched between an active sorority house and a used bookstore. Heather tested at the Red Pass Center in Houston Hall on Wednesday, Dec. 8 after her close friend went into isolation. She received a positive result the following day. On Dec. 9, they took a call from contact tracers in the morning, then messaged Student Health Services (SHS) asking to be placed in Sansom Place West, where their friend was isolating. A few hours later, Heather received an email titled “Your Stay at ADP.” Confused, she marked it as spam. Heather didn’t revisit the email until the next day—they messaged back and forth with SHS, asking when they would receive instructions about isolation and called friends to inquire about the transition to off–campus housing. Both sources told her the same thing: She should have received an email already. It would have been titled “Your Stay at _____.” After digging through her spam folder for the email, Heather packed her bags and moved into the ADPi house on 39th and Spruce. When she arrived at her assigned room, it was filled with “old crap” from the sorority, so she was moved to another one with just “the basics”: a desk and a bed with a thin blanket. Reflecting on her experience, Heather says, “The process of getting to the quarantine dorm could have been more streamlined.” At a point in the school year that was overwhelming for any student, she felt even more lost. The scene at the house was post–apocalyptic. There were no Allied Security guards at any of the entrances, nobody stopping the residents from leaving or inviting people over. Only two other girls had moved in before Heather, and none of them really spoke to one another, opting to stay in their rooms to study for finals or call friends. On their first day, Heather wandered the rooms with the girls, eventually finding themselves in the basement. It was “dank”—a few laundry machines were shoved into a corner, old merchandise was scattered across the floor, and a poster board plastered with fading photos of sorority girls was propped against the wall. For the first few days, Penn tended to the needs of the (at that point) six residents. They received seemingly random calls offering to relocate them and asking if they needed anything. Heather remembers that the University contact helped occasionally—when the residents reported WiFi issues, the reason why students like Maura couldn’t move into the house, they were fixed pretty quickly—but the momentary contact failed to mask the truth of their situation: They were totally alone. The solitude was both exhilarating and daunting. “[Even though] there was no physical support from any campus professionals, … I kind of liked that freedom,” Heather says. She invited over students from other isolation dorms to see the house, and her friends stopped by the entrance to drop off meals from time to time. However, with nobody to check on the residents, their medical condition could escalate without anyone knowing. Heather realized that if she hadn’t brought basic pain medications with her to combat body aches and a runny nose, she might not have been able to treat her symptoms. The lack of supervision also had grimy side effects—there was no way to take out the trash, so ten days worth of waste piled up in the kitchen, emitting an odor that could be detected throughout the house. And with no authority presence, the residents “could have left at any point.” Near the end of the isolation period, this actually happened. One of Heather’s housemates abandoned the house a few days early to spend a night in the Quad—which she could still access with her PennCard—before traveling home. A few days later, Heather exited on time with their belongings, simply walking out the front door. Heather reflects on their experience in isolation with grave maturity. When we speak on Jan. 6, she still has one final exam to take in the spring, and she nurses a runny nose—a lingering symptom from COVID–19. They recognize that vaccines are not a fix–all—they plan on getting tested more often in the spring semester and being more careful about their social activity. “I didn’t realize that a lot of people, myself included, were undervaluing the severity of the pandemic,” she says. “I still feel like I’m suffering the consequences.”

“

The most difficult part was missing school. I missed three final exams in isolation, and now I have three incompletes until I take them in the makeup period. The University almost put me on a mandatory leave of absence and I had to explain my situation to the Committee on Undergraduate Academic Standing.

Sophie Mwaisela, C'24

”

I slept most of my isolation—not because I had symptoms, but because I didn’t want to be left with my own thoughts. This was the most frustrating part. Fortunately, I was placed in a sorority house that had no guards, so I was able to roam the house if I felt trapped in my room. The people that I did see dropped off food for me, and it was quite upsetting because either they were scared to get close to the building or you could only talk to them with a door in between.

Kayleigh Mooney, C'25

“

The hardest part was not knowing that if I dropped dead anyone would know. The support from Penn (besides the lovely telenurse Hilary who checked up on me a couple times) was so scarce and apathetic. It felt like the University didn’t care about me—they only cared about if I transmitted the virus to anyone, which they didn’t even do a good job at controlling. For example, during my time at Sansom I had to leave my room every day to get my food, putting the graduate students that lived there, the security guards, and the front desk workers at risk. I was so scared I would give it to anyone. That, along with the lack of support from Penn, made it one of the worst experiences of my life.

Trevor Arellano, C'24

Note: the quotes above have been edited and condensed.

COVID–19 corroded my body—I missed a late midterm when I first became symptomatic and gave a final presentation after taking a few Advil, through gritted teeth. I hardly left my bed, succumbing to aches and full–body chills, and I couldn’t eat or sleep. When I rose to take a shower in the morning, I grabbed the wall for support, afraid I’d fall because my body was so weak. As students move back to campus, Penn estimates that one in six will have been infected with the Omicron variant over winter break, and the data looks bleak. According to Public Health guidance as of Jan. 10, 2022, students living in the College House system will only need to isolate for five days should they test positive for COVID–19, reintegrating into campus life during the day. The positivity rate for the week 1/2/2022–1/8/2022, before students were originally supposed to have moved back to campus, was 13.22%. Whether Penn has enough space in its isolation buildings remains unclear; we reached out to several departments at Penn about the location of COVID–19 isolation for students in the spring semester, but received no answer as to where students living in on–campus housing who test positive upon return to campus would be relocated. I exited isolation with elation and trepidation. Almost nothing had changed on campus, except my friends were gone, I’d never had a “last day of class,” or what it was supposed to be, and people seemed a lot happier to see me than normal (lots of “you made it!”s). In less than 24 hours, I unpacked and repacked my bags, did an unholy amount of laundry, returned my library books, and boarded a plane home. Memories of time spent in isolation linger even after COVID–19 symptoms are long gone: long days spent in the same four walls, no control over the food being delivered to you, constantly bombarded with confusing and conflicting information—or worse—receiving no information at all. Penn did not seem prepared for the vast uptick in cases correlated with concerns about the emergence of the Omicron variant in November and December 2021; the main side effect was damaging and devastating conditions for those who had to isolate. Heather spent the last days of her fall semester in the shell of a sorority house. Paola was left wondering if she’d make it home to her family for Christmas. Maura was jerked around and displaced, then left alone with spiraling thoughts and a deep sense of disconnection. “It just shows that Penn isn’t as prepared as they seem. They completely dropped the ball on this,” says Maura. A few days before I returned to campus in the spring, my 17–year–old sister tested positive for COVID–19. Since the rest of my family tested negative, my sister isolated in her room, only a wall and a shared bathroom separating us. We brought her home–cooked meals, Publix–brand ice cream sandwiches, books, and our dog, and called her to stave off boredom (or just shouted through the walls). I didn’t get to see her before I took two rapid tests and caught a flight back to Philadelphia, but I knew she was safe, well–cared for. I couldn’t say the same of my own experience. Last semester’s isolation process was characterized by confusion and miscommunication—4 a.m. phone calls to SHS, roused by a burning pain in my forehead or relentless chills encasing my body, brain fog clouding my friends’ minds during pivotal exams, uncoordinated moves from location to location, following a trail of missed calls and vague emails. But, so were the last two years of heartbreak and solitude. As I move back onto campus (marking the fourth time I’ve had to unpack my suitcase in the past month), I carry the memories of my weakened body, liberating long walks, restless nights, and the cold, bright bite of winter air the morning I walked free.

Photo courtesy of Sienna Robinson

Video courtesy of Asger Thieden Maarbjerg